Planning Poker Slideshare

Planning poker, also called Scrum poker, is a consensus-based, gamified technique for estimating, mostly used to estimate effort or relative size of development goals in software development. In planning poker, members of the group make estimates by playing numbered cards face-down to the table, instead of speaking them aloud. The cards are revealed, and the estimates are then discussed. By hiding the figures in this way, the group can avoid the cognitive bias of anchoring, where the first number spoken aloud sets a precedent for subsequent estimates.

Planning Poker relies on relative estimating, in which the item being estimated is compared to one or more previously estimated items. It is the ratio between items that is important. An item estimated as 10 units of work (generally, story points) is estimated to be twice as hard as an item estimated as 5 units of work. Planning Poker Gabriel Rubens @gabrielrubenss http://gabrielrubens.com.br.

Planning poker is a variation of the Wideband delphi method. It is most commonly used in agile software development, in particular in Scrum and Extreme Programming.

The method was first defined and named by James Grenning in 2002[1] and later popularized by Mike Cohn in the book Agile Estimating and Planning,[2] whose company trade marked the term [3] and a digital online tool.[4]

Process[edit]

Rationale[edit]

The reason to use planning poker is to avoid the influence of the other participants. If a number is spoken, it can sound like a suggestion and influence the other participants' sizing. Planning poker should force people to think independently and propose their numbers simultaneously. This is accomplished by requiring that all participants show their card at the same time.

Equipment[edit]

Planning poker is based on a list of features to be delivered, several copies of a deck of cards and optionally, an egg timer that can be used to limit time spent in discussion of each item.

The feature list, often a list of user stories, describes some software that needs to be developed.

The cards in the deck have numbers on them. A typical deck has cards showing the Fibonacci sequence including a zero: 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89; other decks use similar progressions with a fixed ratio between each value such as 1, 2, 4, 8, etc.

The reason for using the Fibonacci sequence instead of simply doubling each subsequent value is because estimating a task as exactly double the effort as another task is misleadingly precise. A task which is about twice as much effort as a 5, has to be evaluated as either a bit less than double (8) or a bit more than double (13).

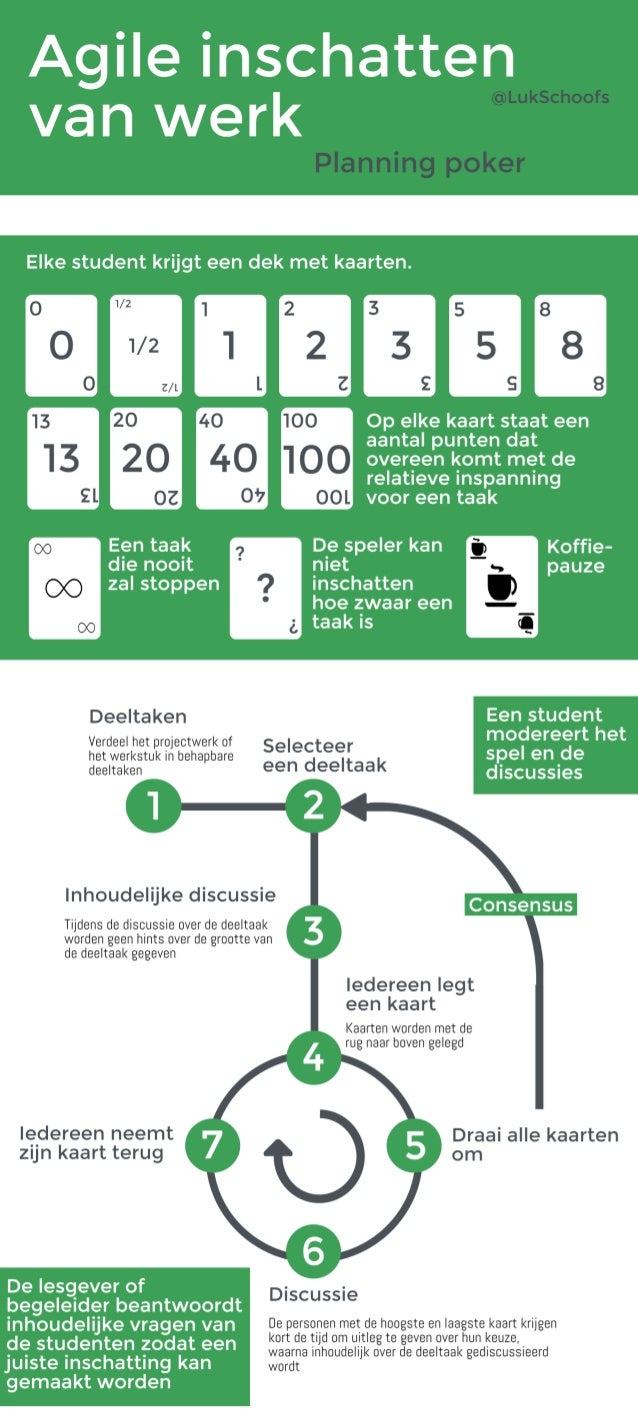

Several commercially available decks use the sequence: 0, ½, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 20, 40, 100, and optionally a ? (unsure), an infinity symbol (this task cannot be completed) and a coffee cup (I need a break, and I will make the rest of the team coffee). The reason for not exactly following the Fibonacci sequence after 13 is because someone once said to Mike Cohn 'You must be very certain to have estimated that task as 21 instead of 20.' Using numbers with only a single digit of precision (except for 13) indicates the uncertainty in the estimation. Some organizations[which?] use standard playing cards of Ace, 2, 3, 5, 8 and king. Where king means: 'this item is too big or too complicated to estimate'. 'Throwing a king' ends discussion of the item for the current sprint.

Smartphones allow developers to use mobile apps instead of physical card decks. When teams are not in the same geographical locations, collaborative software can be used as replacement for physical cards.

Procedure[edit]

At the estimation meeting, each estimator is given one deck of the cards. All decks have identical sets of cards in them.

The meeting proceeds as follows:

- A Moderator, who will not play, chairs the meeting.

- The Product Owner provides a short overview of one user story to be estimated. The team is given an opportunity to ask questions and discuss to clarify assumptions and risks. A summary of the discussion is recorded, e.g. by the Moderator.

- Each individual lays a card face down representing their estimate for the story. Units used vary - they can be days duration, ideal days or story points. During discussion, numbers must not be mentioned at all in relation to feature size to avoid anchoring.

- Everyone calls their cards simultaneously by turning them over.

- People with high estimates and low estimates are given a soap box to offer their justification for their estimate and then discussion continues.

- Repeat the estimation process until a consensus is reached. The developer who was likely to own the deliverable has a large portion of the 'consensus vote', although the Moderator can negotiate the consensus.

- To ensure that discussion is structured; the Moderator or the Product Owner may at any point turn over the egg timer and when it runs out all discussion must cease and another round of poker is played. The structure in the conversation is re-introduced by the soap boxes.

The cards are numbered as they are to account for the fact that the longer an estimate is, the more uncertainty it contains. Thus, if a developer wants to play a 6 he is forced to reconsider and either work through that some of the perceived uncertainty does not exist and play a 5, or accept a conservative estimate accounting for the uncertainty and play an 8.

Benefits[edit]

A study by Moløkken-Østvold and Haugen[5] reported that planning poker provided accurate estimates of programming task completion time, although estimates by any individual developer who entered a task into the task tracker was just as accurate. Tasks discussed during planning poker rounds took longer to complete than those not discussed and included more code deletions, suggesting that planning poker caused more attention to code quality. Planning poker was considered by the study participants to be effective at facilitating team coordination and discussion of implementation strategies.

See also[edit]

- Comparison of Scrum software, which generally has support for planning poker, either included or as an optional add-on.

References[edit]

- ^'Wingman Software Planning Poker - The Original Paper'. wingman-sw.com. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ^Mike Cohn (November 2005). 'Agile Estimating and Planning'. Mountain Goat Software. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ^'Planning poker - Trademark, Service Mark #3473287'. Trademark Status & Document Retrieval (TSDR). 15 January 2008. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^Cohn, Mike. 'Planning Poker Cards: Effective Agile Planning and Estimation'. Mountain Goat Software. Mountain Goat Software. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^K Moløkken-Østvold, NC Haugen (10–13 April 2007). 'Combining Estimates with Planning Poker—An Empirical Study'. 18th Australian Software Engineering Conference. IEEE: 349–58. doi:10.1109/ASWEC.2007.15. ISBN978-0-7695-2778-9.

- Mike Cohn (2005). Agile Estimating and Planning (1 ed.). Prentice Hall PTR. ISBN978-0-13-147941-8.

I published this on my work’s internal blog last week.

Next in my short series on supporting agile practices is planning poker (sometimes called the planning game).

Planning poker may be used when estimating the relative size of a user story, during backlog refinement or sprint planning.

How to play

Let’s assume that a team wants to use planning poker to agree on estimates during a backlog refinement session. They take a look at the backlog and the next story they have to discuss reads, “As a buyer I want to use PayPal to pay for purchases so I don’t need to enter my credit card details into a website I’ve never used before”.

The team discusses with the product owner and any customers or business ambassadors available the ins and outs of the story to fully understand what is required. They craft some acceptance criteria which will help guide them during development and testing.

Once the team feels they understand enough about the story to estimate how much effort and time will be involved they reach for their planning poker cards.

Their planning poker cards use an adapted Fibonacci sequence: 0, ½, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 20, 40, 100. It also includes an infinity card (for impossibly huge tasks), a question mark and sometimes one with a cup of tea that indicates that they feel they need a break.

In a previous session, the team had defined for themselves what they understood a typical 1, 2, 3 and 5 story looks like. They each use this as a guide when deciding on their estimate.

Each member of the team evaluates what they’ve understood about the story against their experience, the effort they think is required, the risk and uncertainty still contained within the story and how long they think the story will take to develop. They each, secretly select a card.

“Well, this seems to me to be a…,” starts Jonny.

The scrum master cuts him short. “No discussion until after the first vote, Jonny, remember?”

“Oh yeah, sorry,” says Jonny and focuses on his cards again.

The scrum master looks around the room. “Is everyone ready?” he asks.

Everyone nods.

“Three, two, one, go!”

And with that everyone spins their card around to reveal a number. There is one 2, four 5s, a 13.

The scrum master then asks the outliers, those who had scored it the lowest and highest, to explain why they had scored that way.

Danny explains that he thought it was a 2 because he’d worked on a similar story with one of the other feature teams a few months ago. He thought it would be a simple case of adapting their code, taking into account a little overhead of generating new credentials, etc.

Louise points out that that other application was on a separate server and there might still be some network and firewall configurations to be done to open up the ports to the PayPal API.

“Ah yes, thanks Louise,” says Danny, “I’ve forgotten about that.”

“Andy,” says the scrum master, “Why did you think it was a 13?”

Andy explains that he’s a very junior developer and while he understands what is being asked to do he has no experience of working with online payments and isn’t entirely sure of the security elements involved. “I’d be happy to pair programme, though,” he says, “so I could learn it.”

“Shall we vote again?” asks the scrum master.

Everyone nods and turns back to their cards.

Planning Poker Slideshare Download

“Three, two, one, go!” says the scrum master again.

This time there are five 3s and one 5. Andy, the junior developer had changed his 13 to a 5.

“Andy, would you be happy with a 3?”

“Erm, sure…” says Andy, with a little uncertainty.

“It’s okay,” reassures Aileen, “we wouldn’t expect you to work on this on your own. We’ll pair for this story anyway.”

“That’s a good idea,” says the scrum master (who oddly doesn’t yet have a name in this little drama and so I’m not going to start giving them one now!) and makes a note of that on the card in Jira.

“Okay, we’re agreed that it’s a 3?”

Everyone nods.

“How sure are you about this estimate, 50/50 or 90%?”

Everyone says 90%.

“That sounds good,” says the scrum master and adds 3 story points to the Jira card.

Why planning poker is useful

The main benefits in using planning poker, in my experience, are two-fold: 1) initial estimates can be made independently, without influence from other developers, and 2) it levels the playing field so that everyone has a voice.

Many of us will have been in teams or groups where there is someone who dominates the group; they are very vocal and have an opinion on everything. Many of us will also have been in groups where we are the newbie and may feel a sense of intimidation by older and/or more experienced group members. Planning poker tries to remove those elements of intimidation or influence by requiring team members to come to their own conclusions before there is any discussion—it gives everyone a good platform from which to start.

Similarly, because everyone has a secret vote it levels the playing field. Everyone at some point will always reveal the lowest or highest estimate. This approach gives everyone, from the most junior to the most senior engineer an equal voice.

My experience

I remember the first time I introduced planning poker to my team at St Andrews. We had just hired a new junior developer to join our team of three; he’d been in the job for about a month.

The user story was about re-architecting an area of the University website, maybe 20 or so pages. To my mind it seemed like a pretty straight-forward task.

Planning Poker Slideshare Tutorial

We voted: 13, 13, 13, 100.

Duncan, the new guy, had voted 100. Once we explain to him how simple this is, I thought to myself, he’ll understand that it’s not a 100. He’s just new, I thought.

“Why did you think it’s a 100, Duncan?” I asked.

“Well, I’ve just been in that section of the media library, while working on a support call and it’s a mess! There is no consistency in folder or file names, I’m sure a lot of the files are in the wrong folders, the actual files have spaces in the filenames and none of them follow our style guide for filename standards. I mean… it’s a real mess. And there are maybe… 300, 400 files. There’s no easy way to see if any are duplicates or are even up-to-date.”

I immediately appreciated why planning poker works. Duncan could easily have been influenced by our prejudices about how easy the task was and gone along with our much lower estimates. We could very easily have dismissed his higher estimate based on our prejudices about him being a new developer. But this levelled the playing field and gave Duncan a voice.

When we re-voted everyone revealed a 100.

Conclusion

I have found planning poker to be a really helpful tool that gives everyone a voice, allows the whole team to get involved and facilitates conversation.